In "Spooking Yourself: Confirmation Bias, Consensus Building, and Household Myth-Making," Karl Sherlock explains one of the most frequent pitfalls in claiming to witness paranormal activity, and warns against two of the most common behaviors that result from it, manufacturing consensus and collaborating on household myths.

There’s an adage spoken among paranormal investigators: If you wish to see a ghost, look about you.

Okay, I plagiarized the Michigan state motto for the cadence of that phrase, but its truism stands true: the more you anticipate witnessing a ghost, the more likely you are to engineer your own experience of one. Put plainly, you can spook yourself into it.

Say, for instance, you were startled by a fleeting something in the periphery of your vision, floating in front of the linen closet at the end of a dimly lighted hallway. You start paying more attention to the periphery of your own vision and, guess what? It happens again, and again. Gotta be ghost, you think, and you start to rationalize it: maybe it’s actually trying to get your attention, and that whole furtive corner-of-your-eye thing is because its wary of you in its space. But, why that space? Is it attached to that antique counterpane you bought at the consignment shop? Is it unable to cross over—whatever that means? You start to surveil the linen closet pretty closely, and suddenly all those creaking sounds you took for house settling make you wonder, Has anyone else noticed besides me? You go ahead an ask, and you get hesitant responses like, “Now that you mention it….” But then you also remember that time Aunt Ellen thought she saw something glowering at the window? And Patches barked for no reason that night at the stained antimacassar on Grandpa's rocker. Oh, and when Delores comes to visit, she always feels like she's being watched (even though she mentioned it only once). Could all of those have been the same ghost in the corner of your eye (hashtag “gitcoye,” as you're now tweeting everyone about it)?

A Primal Rationale

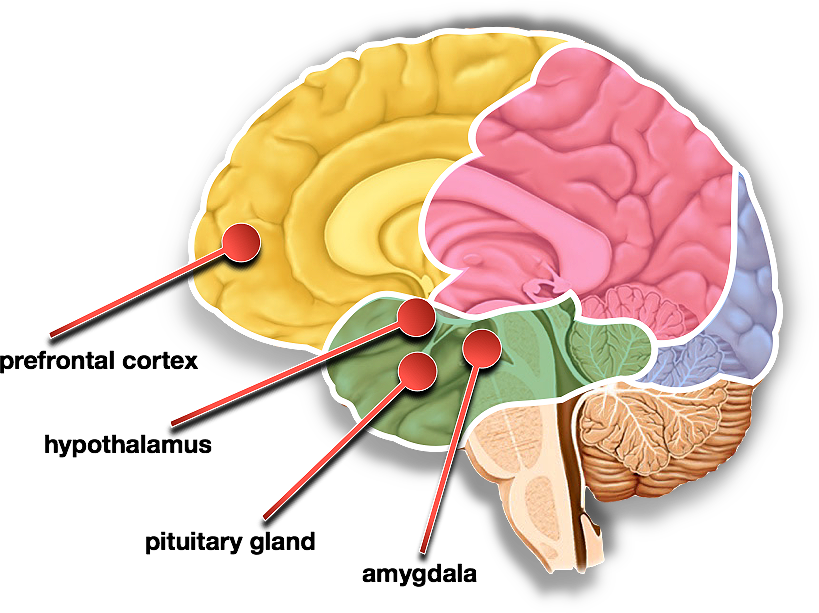

Fitting or retro-fitting our inexplicable experiences to read as paranormal phenomena isn't exactly new to the Zeitgeist. Superstitions and legends have served an etiological function for as long as human history has been recorded, which is a fancy way of saying they provided unscientific explanations for life's mysteries to satisfy our inquisitive urges. Our science and critical thinking skills have evolved, and civilization has apparently outgrown all those supernatural wonders in our folk literature that now seem less instructive than they are entertaining. However, we can't ignore or change the fact that we're primates. Our primate physiology and psychology are frequently at odds with our higher reasoning and all those considerable demands of civilized behavior. When primitive urges arise in us, our frontal lobe compels us to temper them with rational thought—the ol' id v. ego deathmatch—but what we sometimes end up with instead is a primal reaction dressed up merely to look like a rational response, which leads us back in the direction of superstition and folk science. And when it comes to "primal rationale," nothing seems to be as motivating as our fight-or flight response.

|

First characterized by American physiologist Walter Bradford Cannon, the fight-or-flight response, also known as hyperarousal, occurs when you perceive sudden peril. It doesn’t have to be real peril, nor need it be a physical threat. Being shocked by unexpected outcomes, startled by jarring circumstances, or surprised by verbal wit—all of these can induce the fight-or-flight impulse because they’re all degrees of panic that alert your hypothalamus to trigger a stress response. When that happens, your pituitary gland can put you in a cold sweat, and your adrenal glands (located atop your kidneys) can ready you for either the timorousness of Special Projects Director Carter J. Burke or the timerity of Lieutenant First Class Ellen Ripley. If your higher reasoning assures you the perceived peril isn't real, your ambivalent brain subdues the outward expression of your hyperarousal, or vents the stress of it into laughter (which is why people being tickled often clench their fists to strike their attacker, but deflect that urge into fits of giggles). But, if your brain is motivated, not by ambivalence, but by doubt, it cautiously proceeds by checking both boxes, "fight" and "flight," and remains in that state of apprehension. As a result, when you’re in a very agitated state—say, an anomaly on the periphery of your vision—you’re easily spooked by any little thing while at the same time you're stress-responsed to dispatch the danger of it. This is why, when you're apprehensive about the wee ghosties, you're more likely to anticipate paranormal activity and, at the same time, perceive something as confirmation of it. QED: if you want to find a ghost, it's virtually certain you will.

Confirmative Bias

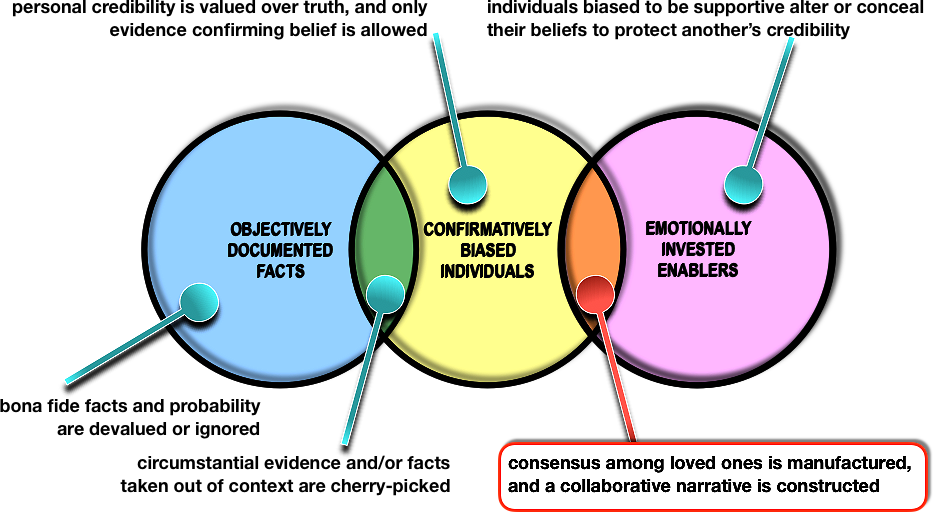

This tendency to see only the things that confirm our belief about it is known as “confirmation bias,” and it’s far from being exclusively a condition of the paranormal. It’s pejoratively known as “wishful thinking,” which doesn’t take into account that we don't always wish for the things we are biased to confirm as real—at least not outwardly. The best fake news stories, for instance, are written and disseminated in a manner capitalizing on our tendency for confirmation bias. Perhaps the best illustration of it is conspiratorial thinking, for which confirmation bias is the modus operandi. Those who believe, for example, that the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre1 was faked are going to opt for the circumstantial details as “evidence” in order to reinforce their belief, but they will disallow those tragic, bona fide facts that don’t reinforce their "theory." U.S. philosopher/logician Willard V. Quine calls this a “web of belief,” woven out of conflicting desires:

The desire to be right and the desire to have been right are two desires, and the sooner we separate them the better off we are. The desire to be right is the thirst for truth. […] The desire to have been right, on the other hand, is the pride that goeth before a fall. It stands in the way of our seeing we were wrong, and thus blocks the progress of our knowledge.2

Because claiming your home is haunted is looney-tunes to a great many people, it's not the search for the truth, but rather the vindication of your belief that becomes an operative motive, even if at a subconscious level only. As a result, a paranormal witness impacted by his experience will often embark on a campaign to build a consensus out of other household members, not in the search for truth about whether there’s a ghost in the house, but rather in an effort to reinforce his own credibility as someone making incredible claims.

Household Myth-Making

PPI investigators refer to this campaign of credibility as “household myth-making,” and it’s one of the most difficult behaviors to address in our cases, because it’s so embedded in the psychology of the household. Family members or roommates will have already spent a period of time processing one person’s confirmatively biased investment in the idea of being haunted. This may evolve into the premise that the person, rather than the dwelling, is the target of the haunting, which conveniently prevents others from an objective look at the phenomenon and disallows evidence that could put the claimant's credibility in jeopardy. Of course, there are two other possible responses, "bunco" or "bonkers": either the witness is making it all up, or a psychological affliction is to blame. The problem is, even if people are thinking it, most will avoid the discomfort of saying it, preferring to seem supportive of a loved one's truth even when it means devaluing their own. Over time, this well intentioned “going along in order to get along” pattern of enabling behavior inevitably develops into a co-dependent one, and before long everyone in the house becomes intractably invested in a collaboratively shaped paranormal narrative.

By way of illustration, PPI answered a case request involving a large military family, which is common in San Diego. Claiming an entity had attached itself to them after a ghost-hunting outing at a cemetery, the parents were very honest about the challenges facing their family during that time. Besides the father being absent for long periods of military duty, the mother’s health condition limited her activities, a younger child’s mild autism meant behavioral difficulties, and three of the other children were already in the throes of adolescence. All the family members had their own experiences, but none were as narratively driven as the adolescent children’s; they included inventive anecdotes about threatening faces staring at them from reflective surfaces, devilishly glowing eyes in the night, inexplicable scratches down their arms upon waking in the morning, a grey lady chasing them down a hallway, and other classic intrigues. The most pronounced of these narratives, however, came from the eldest daughter who, besides claiming to have psychic ability, described in vivid detail a graveling that followed her everywhere, even at school, where it crouched on a desk and oggled her. Needless to say, when your teenaged daughter complains of being psychically stalked by a demonic homunculus, your first response should be either to consult her neurologist, to enlist a counselor for her, or to corner her paramour for a "friendly chat." A paranormal investigative group certainly shouldn't be your go-to response. This was one of many clues that the home's paranormal activity served unwittingly as a "play inside the play" for the family, an interactive theater in which everyone’s shared belief about being paranormally afflicted seemed to hold the entire family together during these troubled times. It was even apparent that two of the children were, with great intention, following their older sibling's lead, as though they were in training, writing their own scripted parts within the family melodrama.

|

This example is not unique among our case files. Nor are its consensus building and household myth-making anything out of the ordinary; you can recognize these tendencies in everything from the infamous Cottingly Fairies to the Enfield Poltergeist (both of which were deemed hoaxes). But, it shows just how potent the positive reinforcement can be for individuals who passively consent to collaborating on a confirmatively biased "story of record." Firstly, a scripted narrative typically makes the house intriguing and the people living in it the protagonists of their own supernatural adventure. (Tres jolie!) Secondly, a residual bond among household members forms out of all that archetypal myth-making narrative about two or more people joining forces to overcome shared adversity, uniting for a common purpose. And, in the case of family households like the one illustrated above, the very idea of a close-knit family becomes dependent on the continued collaboration of family members in that myth. In short, the family that believes together stays together.

When this happens, it’s almost futile for groups like ours to present reasonable explanations or to try to reassure clients that we found nothing paranormal. In fact, those are the wrongest answers possible, because the intention from the get-go had been for us to investigate as a way to reinforce their household myth-making. Once again, as Willard V. Quine suggests, they’ve exploited an interest in the truth in order to appear being right, and we, like the hapless Wicker Man, stumbled voluntarily into their designs.

Parsing Fact from Fiction

Perhaps the greatest difficulty of all in these situations is having to acknowledge that, despite obvious confirmation bias, something anomalous is indeed happening on their premises, even though it might not necessarily fit the characteristics of their household myth (nor be paranormal). After all, as investigators we don’t want to fall into the trap of dogmatic skepticism, which is its own kind of confirmation bias in that it relies strictly on pre-established assumptions, cherry picks only practical explanations, and omits findings investigators are unable to explain. Although in the example cited above there were no findings of interest resulting from the investigation (other than the family psychology, itself), this has often enough been the dilemma in other family cases where the analysis of our data and recorded media actually pointed to something anomalous in the midst of all that household myth-making. While our inability to name a practical or scientific cause wasn't de facto evidence for a haunting, we couldn’t ethically omit those findings from our report just for the sake of deconstructing their family-bonding rituals. Furthermore, although we're ethically bound to disclose our findings in an unbiased way, we struggle with whether or not we have a right to assume PPI's agenda supersedes the client's. Who are we to deny a family a chance to pull itself together and be close? Maybe it’s not what we thought we were signing up for, but that's the risk that comes with voluntarily accepting any case request.

What, then, is the answer? Is there a pragmatic way to avoid confirmation bias, myth-making, and the unwitting exploitation of others it can incur? And, is there a way for investigators to assess in advance of the actual investigation whether or not they will be walking into a family masque?

Well, no—but also yes.

The highly emotional and typically anxious circumstances in which you believe yourself to be haunted are always going to create conditions fertile for confirmation bias. There may actually be something genuinely inexplicable happening to you or around you, but, like hearing a raccoon jumping from branches in the dark, you have to remind yourself it’s not nearly as big as it sounds. A pragmatic and skeptical attitude about it, as well as self-awareness over what drives you to want “proof” of haunting—these are your best defenses against the pitfall of spooking yourself.

Journaling

If you’re looking for outside help, however, and wish to be conscientious about not drawing others into a campaign of household myth-making, one of the best things you can do for yourself and an investigative team is to keep a journal.

A good journal can log crucial information investigators wouldn't be able to collect during the limited hours of their investigation, and it can expose patterns of behavior and activity from which useful correlations might be drawn. It can also serve as an impartial window onto your own experiences, showing you where and when you’re not being as objective as you imagine, and where your own "wishful thinking" might be creeping in. Lastly, a journal can serve as a diary, which is especially important if you have a strongly emotional or anxiously psychological response to what you perceive to be paranormal activity. Some things you’re unwilling to share with other household members you might be more willing to record in a journal, which can be as constructive as it is revelatory.

While it’s never a bad idea to keep an ongoing journal about your paranormal experiences, when you're anticipating a formal investigation each person in the household should try to keep a journal of their own as well, at least for a period long enough to yield a cohort study for the investigative team. Four weeks is a good start.

What should you put in your journal?

- Record all primary identifying info: your name, the date, location, and time (hh:mm) of the occurrence.

- Indicate any relevant secondary information such as weather conditions, notable indoor sounds, street noises, and the like.

- Identify anyone else besides yourself who was present and a witness, as well as those who were present but did not witness the occurrence. If a companion animal was involved, don't forget to include it, but don't ask anyone else keeping a journal what, if anything, they witnessed, since you'll want to avoid consensus building and myth-making.

- Reference and detail any sensory or behavioral anomalies applicable to your experience and describe it in as much practical detail as you can. (See "Journaling Paranormal Activity" in the Client Resources area of this website for a detailed list of criteria and sample journal entries.) Note any distinguishing features; for example, if you witnessed an apparition, indicate whether it was moving or static, did it vanish or dash away, was it solid or translucent, tall and human or short and animal-like, and so on. Also describe any efforts you might have made to find practical, non-paranormal causes for the occurrence.

- Note any possible physiological or emotional factors, such as medications or eyeglasses or moods, that might have been influential to the experience. Try to offer at least one alternative explanation for your experience.

Spooky Good

Keep in mind, in households of two or more, everyone is a participant in your case, even if they’re completely unaware of what’s happening to you. Your claim about paranormal activity either draws others into a shared experience of it, or it draws them into your experience of dealing with it on your own. It can be just as empowering for households to cooperatively journal their experiences as it is for them to collaborate with you on a household myth. The major difference, however, is that the latter is only about the vain pursuit of building consensus, while the former is about honest search of the truth—which turns you away from "primal rationale" and puts you instead on course for credible discovery.

And it pays to be honest with yourself when it comes to paranormal activity. Besides, if you really suspect there’s paranormal activity in your midst, the last thing you need is to spook yourself. Leave that job to the ghosts in your linen closet, and, for Patches' sake, wash those stains out of Grandpa's antimacassar.

1On December 14, 2012, in Newtown, Connecticut, Adam Lanza murdered twenty innocent children and six staff members, as well as his own mother, at the Sandy Hook Elementary School before taking his own life. Fringe conspiracy theorists have attempted to cast doubt on the veracity of this tragedy, some claiming the massacre was arranged by the Barack Obama administration to rally support for more stringent gun control, while others have accused the event of being entirely faked by actors.

2Quine, Willard Van Orman, and Joseph S. Ullian. The Web of Belief. New York: Random House. 133.